First published in 1975, The Machine Gunners was Robert Westall’s very first novel. The story follows a group of north east school children during the Second World War who manage to take the machine gun from a crashed German aircraft. Originally written for Westall’s son, Christopher (who later died in a tragic motorcycle accident), the book draws heavily upon Westall's own childhood on the north east coast (the book is set in fictional 'Garmouth', largely based on Tynemouth where Westall spent the war as a boy). Upon its release, The Machine Gunners was critically acclaimed and brought Westall the first of his two Carnegie Awards. The novel is still a much-loved classic and in 2007 made the list of top ten all time Carnegie winners.

|

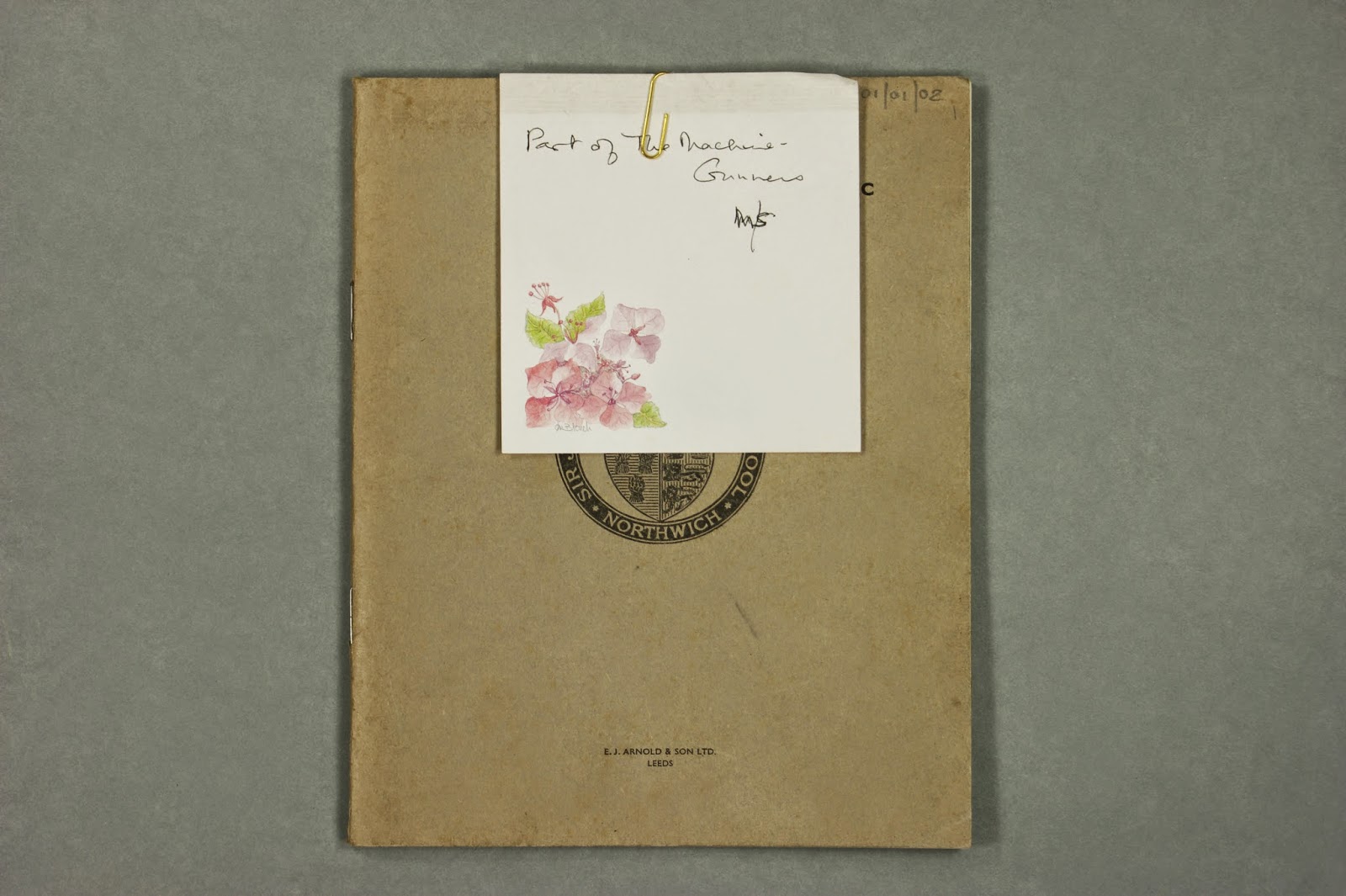

| One of the notebooks in which Robert Westall wrote his manuscript for The Machine Gunners, from the collection here at Seven Stories |

In 1981, six years after the book's publication the production rights were bought by the BBC. Television drama made for children and young people was becoming increasingly popular at this time (Grange Hill had only just made its first appearance three years earlier in 1978) and television companies were eager for stories that had potential for serialisation. The much-loved and critically acclaimed, The Machine Gunners, presented an ideal opportunity for the BBC and they set out to secure the rights for a six part drama.

|

| Letters from the BBC to Robert Westall about The Machine Gunners, from the Robert Westall collection here at Seven Stories |

The first episode aired on 23 February 1983. The script was written by another well-known writer originally from the north east, William Corlett - who, as well as being a script writer and playwright, produced a number of successful novels for children and adults. The series director was Colin Cant, a specialist in children's drama who, as well as serving for many years on Grange Hill, went on to direct other children's book adaptations including Moondial (by Helen Cresswell) and The Children of Green Knowe (by Lucy M. Boston).

The series was well received by audiences and is even now fondly remembered by many. Of the adaptation Robert Westall himself wrote:

"I quite approve of the TV serial made from 'The Machine Gunners'. The script writer was William Corlett, who also writes children's novels. He loved the book very much – perhaps too much, for he could not bear to leave many incidents out, and at times (as in the Mrs. Spalding incident with her knickers), things got a little rushed and blurred. The fault lies with the BBC producers, who did not allow more than six episodes. It takes about ten episodes to do justice even to a children's book, and they just don't seem to have the nerve to allow this many episodes."

('About 'The Machine Gunners'', http://www.robertwestall.com/the_machine_gunners_by_robert_westall.html)

|

| Another of the notebooks in which Robert Westall wrote his manuscript for The Machine Gunners, from the collection here at Seven Stories |

In 2002, The Machine Gunners was again adapted by the BBC but this time for radio. The story has also appeared on stage - in 2011 a stage version was performed at Polka Theatre in London, commissioned by the Imperial War Museum.

The Robert Westall collection is available to consult by appointment at Seven Stories Collections Department. If you'd like to find out more about this collection or others that we hold you can

email: collections@sevenstories.org.uk or phone: 01914952707.

Material from the Seven Stories archive is currently on display at an exhibition looking at the work of Robert Westall at the Friends of Weaver Hall Museum in Northwich, Cheshire: http://www.fowhm.org.uk/events/exhibition-robert-westall-a-writer-and-his-world/

If you'd like to find out more about other children's books adapted for the screen then why not visit our exhibition Moving Stories: Children's Books from Page to Screen at the Seven Stories visitor centre, Newcastle upon Tyne, until April 2015